Volume II: Archaic Ceremonial Monuments

This scholarship was compiled by John Vincent Bellezza through a fellowship for East Asian Archaeology and Early History from the American Council of Learned Societies with funding from the Henry Luce Foundation. The technical work, design, copy editing, and preparation in digital format was done at the University of Virginia by the Tibetan & Himalayan Library with a grant from the Luce Foundation and the US Department of Education TICFIA Program.

In particular, I salute the outstanding expertise of the following individuals involved in the technical work and editing. In alphabetical order:

- Geoffrey Barstow, editing

- Tom Benner, map preparation

- Quentin Devers, editing and map preparation

- Mark Ferrara, web-design

- Nathaniel Grove, technical support

- William McGrath, editing

- Alison Melnick, editing

- Andres Montano, technical support

- David Newman, technical support

- Mickey Stockwell, editing

- Steven Weinberger, editing, technical support, project management

- Michael White, editing

Since 1994, this inventory of pre-Buddhist archaeological sites in Upper Tibet has been made possible through the friendship and cooperation of many fine people. I warmly thank the more than 5000 residents of Upper Tibet who helped guide me to their archaeological heritage and who patiently tried to answer my many questions about them. I cordially acknowledge the assistance and guidance of numerous Tibet Autonomous Region provincial, prefectural, county, and township authorities. Their help was indispensable in the pursuance of my work. Moreover, I could not have comprehensively explored sites throughout the region without the active and sustained sponsorship of the Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences and the Ngari Xiangxiong Cultural Exchange Association. These institutions and the people who work for them command my deep admiration. I also want to thank the crews of drivers, guides, cooks and assistants who accompanied me on most expeditions. They performed in an exemplary fashion in what were challenging circumstances.

The organizations and institutions that financially supported my work over the last twelve years deserve my greatest appreciation and special credit. I simply could not have done my work without their support. I list those who have awarded me grants and fellowships in alphabetical order:

- American Council of Learned Societies in conjunction with the Henry Luce Foundation (New York)

- Asian Cultural Council (New York)

- Kalpa Group (Oxford)

- National Geographic Expeditions Council (Washington D. C.)

- Shang Shung Institute (Merigar)

- Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York)

- Spalding Trust (Stowmarket)

- Tibetan Medical Foundation (Weslaco)

- Trust for Mutual Understanding (New York)

- Unicorn Foundation (Atlanta)

I express profound gratitude to my Tibetan Bön teachers of history and literature: His Holiness Menri Tridzin Ponsé Lama, Loppön Tendzin Namdak and Yungdrung Tendzin. It is also with much pleasure that I extend my thanks to Gene Smith (Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center), Ernst Steinkellner (Universität Wien), David Germano (University of Virginia), and Charles Ramble (Oxford University) for their academic support and friendly encouragement. Finally, I am delighted to acknowledge the goodwill and assistance of John Bellezza (Southampton), Mickey Stockwell (Boulder), Mary Lanier (New York), and Karen Harris (Trinidad). Without the moral support and practical aid of these very fine individuals, my exploratory and scholarly endeavors could not have come to fruition.

The upper portion of the Tibetan Plateau, a land of large lakes, lofty peaks, interminable plains, and deep gorges, stretches north and west of Lhasa for 1500 km. Bound by high mountain ranges on all sides and averaging 4600 m above sea level, Upper Tibet gave rise to an extraordinary civilization in antiquity. Beginning about 3000 years ago, a chain of mountaintop citadels, temples, and intricate burial complexes appeared in this vast region of some 600,000 square kilometers. These monuments were part and parcel of a unique human legacy, which flourished until the Tibetan imperium and the annexation of Upper Tibet by the Pugyel emperors (tsenpo) of Central Tibet. Gradually the unique beliefs, customs and traditions of archaic Upper Tibet yielded to a pan-Tibetan cultural entity that arose in conjunction with Vajrayāna Buddhist teachings.

A millennium ago, Buddhist domination of Tibet spawned a new civilization, one in which the celebrated Lamaist religions of Bön and Buddhism came to hold sway. The inexorable march of time and the ascent of the new religious order slowly but surely clouded the memory of the earlier cultural heritage. As a result, many of the ancient achievements of the Upper Tibetan people were forgotten. All that remains are preserved in the impressive monumental traces of the region. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung attempts to reclaim these past glories by systematically describing the visible physical remains left by the ancient inhabitants of Upper Tibet.

The residential and ceremonial monuments of Upper Tibet, established by what can be termed the “archaic” cultures of the region (Zhang Zhung and Sumpa of the literary records), strongly contrast with those built in the central and eastern portions of the plateau in the same span of time. There are very substantial differences between the archaeological makeup of the archaic cultural horizon (circa 1000 BCE to 1000 CE) and that of the Lamaist era (circa 1000 CE to 1950 CE) in Upper Tibet. The unique monumental assemblage of Upper Tibet delineates the bounds of a paleocultural complex squarely based in the uplands of the plateau. The special physical hallmarks and highland homeland of this ancient culture set it apart from other Bodic cultures, which arose in the central and eastern parts of the Tibetan Plateau. The paleocultural world of Upper Tibet is readily distinguished from those civilizations that appeared in adjoining lands to the south, west and north. In the archaic cultural horizon the Upper Tibetans constructed highly durable all-stone elite residences, temples and castles, developing stone working techniques particularly suited to their extremely harsh natural environment. They also designed and built elaborate burial complexes containing many types of ritual structures made entirely of stone. The use of stone corbelling for the construction of roofs and the erection of pillars in peculiar configurations for ceremonial purposes reached a very high level of proficiency in Upper Tibet. The eminently practical qualities of this architecture have helped to insure that the remains of a surprising number of monuments have endured to the present day.

Although the design and construction of the monumental assemblage of archaic Upper Tibet is highly distinctive, affinities with other archaeological cultures of the plateau and steppes certainly exist. During the first millennium BCE and first millennium CE, a tremendous amount of cross-fertilization occurred throughout Inner Asia. These manifold cultural links are explored in depth in my last book, Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. This monograph furnishes the analytical framework and data necessary to begin to comprehend the chronological, economic and cultural dimensions of the sites surveyed in the present work.

Antiquities of Zhang Zhung systematically describes the physical remains of 404 Upper Tibetan monumental sites documented since 2001.1 It is an inventory of archaic or prospective archaic archaeological sites. These sites differ from Lamaist monuments in terms of morphology, function, mythology, and geographic orientation. This catalogue of archaeological sites should prove useful to scholars working in a variety of disciplines. As a reference work, it is well suited to provide a perspective for subsequent studies devoted to better understanding the archaic physical and cultural environment of Upper Tibet and other regions of Inner Asia. It presents uniform sets of physical and cultural data for each of the sites surveyed to produce a coherent view of the monumental vestiges scattered across the Upper Tibetan landscape. As a compendium of archaeological sites, this work is primarily quantitative (descriptions of the remaining physical evidence) in nature. To a lesser degree, it also provides qualitative information (analyses of the ideological groundwork underlying the physical manifestations) in order to elucidate various abstract aspects of the monuments. This methodological approach, borrowing from archaeological, literary and ethnographic sources of information, permits an integral picture of ancient Upper Tibetan archaeological assets to emerge. By bringing Upper Tibet’s fascinating past into clearer focus, we begin to acquaint ourselves with the formative elements in the development of Bodic civilization. In turn, this permits us to move one step closer to understanding the Tibetan Plateau’s place in the Eurasian cultural mosaic of yore.

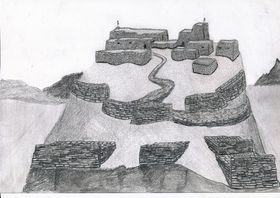

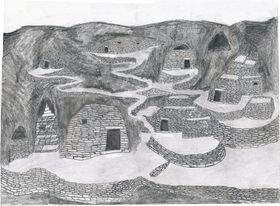

An inspection of the sites surveyed opens a window onto a remarkable Tibetan heritage. Rather than a cultural backwater, upland Tibet emerges as a nexus of technological and cultural brilliance. A chain of citadels circumscribing the region reflects the existence of a vibrant social order in which agriculture played a vital role. From the first millennium BCE onwards, a warrior and priestly elite appears to have founded and occupied these citadels. The sheer number of fortified sites built on summits shows that martial struggle was a prominent preoccupation (which is mirrored in the Tibetan literary record). The top strata of ancient Upper Tibetan society constructed all-stone temples and residences in which the cultural life of the region reached a crescendo. Troglodytic communities sprang up wherever there were natural caves or where it was possible to excavate earthen formations. In the cultural hothouse environment of first millennium BCE and early first millennium CE Inner Asia, Upper Tibet appears to have been one of several regions with superior intellectual and military capabilities. The legendary status accorded Zhang Zhung in Tibetan literature buttresses the archaeological record, indicating that Upper Tibet had indeed reached a considerable level of human attainment before the spread of Buddhism.

The existence of intricate burial rites is echoed in the many tombs and necropoli that dot the entire region. These architecturally diverse funerary sites allude to sophisticated eschatological concepts and practices prevalent in early Upper Tibet. The mortuary archaeological evidence also records yawning divisions in wealth and social status, a sign that the region possessed a hierarchical society with deep social, economic and political divisions. This puts the highland variant of Bodic civilization in line with surrounding civilizations of the Iron Age and the classical period, where social stratification, economic diversification and warfare were rampant. While many linkages between the empirical and textual perspectives remain hypothetical, the intellectual profundity of matters related to death in both the literary and archaeological records is unmistakable and very significant. In Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet, I examine the interconnections between the mortuary sites of Upper Tibet and the archaic funerary beliefs and rituals of the Tibetan texts.2

So much still needs to be discovered before we can find answers to even basic questions concerning the polity and people of ancient Upper Tibet. Nevertheless, the good news is that step-by-step an understanding of the region’s archaeological character is being secured. This increase in our knowledge should pave the way to new insights into the origins and development of Tibetan civilization, as well as to a more refined appreciation of the ancient cultural complexion of Inner Asia. It is in the service of such aims that the present work has been composed.

- ^ For the findings of my earlier expeditions see: Bellezza, Antiquities of Upper Tibet; Bellezza, “Gods, Hunting and Society: Animals in the Ancient Cave Paintings of Celestial Lake in Northern Tibet,” East and West 52 (2002): 347-396; Bellezza, Antiquities of Northern Tibet; Bellezza, “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet,” Rock Art Research 17, no. 1 (2000): 35-55; Bellezza, “A Preliminary Archaeological Survey of Da rog mtsho,” The Tibet Journal 24, no. 1 (1999): 56-90; Bellezza, “Notes on Three Series of Unusual Symbols Discovered on the Byang thang,” East and West 47, nos. 1-4 (1997): 395-405; Bellezza, Divine Dyads.

- ^ Another crucial archaeological asset of Upper Tibet is rock art, which provides a rich record of the archaic way of life in the region. Dozens of sites in which petroglyphs and pictographs document social, religious and economic facets of early life are distributed over much of Upper Tibet. This graphic evidence also reveals the existence of a distinctive paleoculture, one with strong affinities to surrounding peoples but with its own idiosyncratic qualities, setting Upper Tibet apart from the steppes and more eastern regions of the plateau. Rock art, a prime indicator of aesthetic values, defines the uniqueness of early Upper Tibet as much as its monumental assemblages. The rock art tableaux spectacularly depict the vitality, resourcefulness and stamina of the past inhabitants of the region. This is certainly something that modern day Tibetans can take pride in and something in which the rest of the world can marvel. A comprehensive inventory of Upper Tibetan rock art was also conducted and will constitute the contents of another volume in the present series in due course.

1I began my travels in Upper Tibet (Jangtang and Tö) in the mid-1980s, a golden period in the exploration of the plateau. This was an exciting time for discovery in Tibet, a time when a small group of explorers (curiously, they were mostly from English-speaking countries) reached places never before visited by foreigners. During my initial years of peregrination in Upper Tibet, I began to notice unusual manmade formations and ruins but did not pay much attention to them. In the early 1990s, having acquired the requisite cultural and linguistic skills, I turned much of my scholarly energy to the documentation of archaeological remains and the elucidation of the ancient cultural history of Upper Tibet. In the course of fieldwork, I have had the good fortune to visit every county and virtually every township in the great Tibetan upland north and west of Lhasa. These archaeological surveys in the region have therefore proven geographically all-inclusive.

On earlier visits to Upper Tibet, an immense region of approximately 600,000 km², I spent a great deal of time on foot and solo. On more recent expeditions, I have depended on motor vehicles and crews to expedite reaching highly remote places and the process of documentation. Despite having vehicles, fairly long distances still had to be hiked or ridden on horseback due to the rugged nature of the terrain. Many sites located on mountaintops and escarpments, or in gorges and caves are only accessible on foot. The physical rigors of these expeditions should not be underestimated. Upper Tibet is a tough environment in which to work and the pace of study has been intensive.

- ^ Much of this section of the work was taken from the text of Bellezza, Zhang Zhung.

- 1992: Four Fountains of Tibet Expedition (FFTE)

- 1994: Divine Dyads Expedition, year one (DDE1)

- 1995: Divine Dyads Expedition, year two (DDE2)

- 1997: Changthang Phase II Expedition, year one (CPE1)

- 1998: Changthang Phase II Expedition, year two (CPE2)

- 1999: Changthang Circuit Expedition (CCE)

- 2000: Upper Tibet Circumnavigation Expedition (UTCE)

- 2001: Upper Tibet Antiquities Expedition (UTAE)

- 2001: Shang Shung Institute Expedition (SSI)

- 2002: High Tibet Circle Expedition (HTCE)

- 2003: High Tibet Antiquities Expedition (HTAE)

- 2004: High Tibet Welfare Expedition (HTWE)

- 2005: Tibet Upland Expedition (TUE)

- 2006: Tibet Ice Lakes Expedition (TILE)

- 2006: Tibet Highland Expedition (THE)

- 2007: Wild Yak Lands Expedition (WYLE)

In 2001, I launched the four-month long Upper Tibet Antiquities Expedition (UTAE), which clocked around 8500 km in vehicles and significant distances on foot and on horseback. On the UTAE, 90 archaeological sites were documented in Baryang, Purang, Khyunglung, Gugé, Chusum, Götsang, northern Rutok, Naktsang Rongmar, and Dangra Yutso. In 2002, I set off on the High Tibet Circle Expedition (HTCE), which was of four months duration as well.1 This expedition yielded information on more than 100 archaeological sites, the overwhelming majority of which had never been documented. On the HTCE, I covered 13,200 km by motor vehicle, and trekked considerable distances on foot and on horseback. The main thrust of exploration included Baryang, Langa Tso, Gang Rinpoché, Zarang, Rutok, northern Gertsé, Ngangla Ringtso, Tsochen, Dangra Yutso, the Tago range, and Barta. In 2003, I conducted exploration on the High Tibet Antiquities Expedition (HTAE), which lasted 48 days.2 On the HTAE, around 40 archaeological sites were documented by traveling more than 8000 km by motor vehicle. The geographic focus of exploration was the border areas situated in Rutok, Tsamda and Purang, marking the first access to many of these sectors by an outsider in 60 years.

In 2004, I launched a three-month mission to Upper Tibet called the High Tibet Welfare Expedition (HTWE). The HTWE was carried out with the purpose of reconnoitering areas of Upper Tibet not previously visited or where more inquiry was required. The main areas for research and exploration included Damzhung, Yakpa, southern Tsonyi, Dangra Yutso, Tsochen, Senkhor, Zhungpa, Rutok, Gar, and Tsamda. In 2005, I embarked on the 45-day long Tibet Upland Expedition (TUE), in order to survey sites across the breadth of much of Upper Tibet not reached on earlier campaigns. By continually making forays, I have been able to close the gaps in the geographic coverage of the region. Slowly but surely, I have now visited most of the major basins and valleys of Upper Tibet south of the 33rd parallel.

In the winter of 2006, I conducted the four-week long Tibet Ice Lakes Expedition (TILE) in order to reach six islands in four different lakes. By traversing the frozen surfaces of the lakes, I was able to survey Semodo (Namtso), Dotaga and Dodrilbu (Daroktso), Tsodo (Tsomo Ngangla Ringtso), and Doser and Domuk (Langak Tso). In the spring of 2006, I completed the basic survey work, a 12-year enterprise. Known as the Tibet Highland Expedition (THE), the object of this 46-day 2006 excursion was to carry out reconnaissance in the northern Jangtang, and to visit a few outstanding archaeological sites. In 2007, on the Wild Yak Lands Expedition (WYLE) (45 days in length), I reconnoitered parts of the northern Jangtang and documented a handful of archaic sites in Gugé and other locations.

In surveys conducted since 2001, I have endeavored to expand and strengthen the methodological tools at my disposal. It has been necessary to further systematize the collection of data and to articulate these in forms that make it accessible to a wider range of Tibetologists, archaeologists and cultural historians. The survey data thus compiled have permitted the various types of archaeological assets present in the region, their patterns of distribution, environmental context, and structural qualities to be elucidated in greater clarity. Another vital component of this appraisal of Upper Tibetan archaeological sites has been the compilation of chronometric data derived from the radiometric and AMS assaying of organic samples. To date, 21 samples have been submitted for chronometric testing and analysis, permitting the initial direct dating of a few documented sites. This augmented methodological approach to the survey work has enabled the positioning of the sites chronicled within a more refined chronological context, opening the way to new perspectives in the study of Tibetan textual sources. Generally speaking, these breakthroughs in the study of Upper Tibetan cultural development pertain to temporal controls, which encompass both the prehistoric and historic epochs.

The methodological regimen applied to the survey of monuments (residential and ceremonial) can be summarized as follows:

- The pinpointing of the geographic coordinates, elevation and administrative location of each site. The determination of latitude, longitude and elevation was accomplished with the use of a GPS. In locating sites, reference is made to toponymic nomenclature employed in both historical (traditional) and Communist (modern) political geography.

- A description of the geographic and ecological settings of archaeological sites. In order to understand the physical environment shaping the function and placement of monuments, attention has been paid to slope gradients, general soil conditions, prominent landforms in the proximity, geomorphologic changes, and the endowment of natural resources.

- The identification of the monumental types found at each archaeological site. This is carried out using a comprehensive typology of above-ground archaeological resources devised for Upper Tibet (see Section 5).

- An analysis of the morphological, design and constructional traits of each structural component of an archaeological site. A study of how monuments were built and the types of materials that went into their construction is vital in differentiating the various typologies. The investigative focus has been directed towards determining ground plans, wall fabrics, the rendering and presentation of structures, patterns of usage, and the spatial arrangements of the various structural components making up a site.

- The measurement of site dispersals and the dimensions of constituent structures. The overall extent of sites (measured in square meters), and the length, width, height, and girth of monuments and their respective components.

- The mapping of monuments (plans and topographic settings). Save for sketches of a few ground plans, the cartographic dimension has thus far been limited to overview and typological maps of archaeological sites.

- The photography of the general settings of sites, all visible archaeological remains, and the current cultural scene.

- The compilation of folklore, myths, legends, and historical accounts surrounding archaeological sites. I have endeavored to collect the local oral traditions attached to the monuments surveyed in order to gain a firmer understanding of the chronology, function and significance of sites as conceived by indigenous sources.

- The collection and translation of Tibetan textual sources pertinent to the function, cultural make-up, political affiliation, and chronology of monuments and the physical sites in which they are located. This facet of study defines the interface between empirical and traditional historiographic approaches to understanding Upper Tibet’s archaeological heritage.

- An assessment of contemporary anthropogenic and environmental risks to the continued survival of archaeological monuments. This proactive component of research concerns issues related to the conservation and sustainability of archaeological assets.

The interrelated methodological regimen used in the surveys of rock art can be summarized as follows:

- The pinpointing of the geographic coordinates, elevation and administrative location of each rock art site.

- A description of the geographic and ecological settings of rock art sites.

- An analysis of the physical characteristics, relative locations and techniques of manufacture of rock art.

- The measurement of rock panels and individual compositions.

- The mapping of rock art sites (geographic locations).

- The photography of the general settings of rock art sites, individual compositions and the current culture-scape.

- The compilation of folklore, myths, legends, and historical accounts surrounding rock art sites.

- The collection and translation of Tibetan textual sources pertinent to the function, cultural orientation, political affiliation, and chronology of rock art sites and individual compositions.

- An assessment of contemporary anthropogenic and environmental risks to the continued survival of rock art.

I have undertaken to document every visible archaeological site of the archaic cultural horizon on the vast Tibetan upland and, while falling short of this ambitious goal, more than 600 monumental sites and 50 rock art sites have been surveyed throughout the region. How many other archaic sites with visible above-ground footprints exist in Upper Tibet remains to be determined. In particular, there must be many dozens of ancient burial grounds that have yet to be charted. This is indicated by the sheer number of tombs already documented, the oral tradition that holds that tombs are distributed all over Upper Tibet, and the practical difficulties in locating structures with little or no protrusion above the ground surface. The geographical thoroughness of the survey work, however, indicates that a statistically significant cross-section of monument types and rock art has been documented.

Over 90% of the sites chronicled in this inventory have not been identified or studied by other research teams. Rather than the application of remote sensing tools and aerial surveys to identify archaic cultural horizon archaeological assets in Upper Tibet, I took upon myself the laborious and time-consuming task of comprehensive field inspections. Visible detection of sites was facilitated in most places in Upper Tibet by poorly developed alpine and steppe soils, sparse vegetation cover, and high rates of surface erosion. As in any region, a percentage of the total number of Upper Tibetan archaeological assets is not amenable to surface detection. The percentage of sites that were overlooked because of the lack of visual apprehension, however, appears to be relatively low in the Jangtang (given its prevailing topographic and vegetative features). Conversely, in the badlands of Gugé, a region of thick alluvial deposits and the regular occurrence of landslides, a much higher percentage of archaeological remains are probably obscured from view. A significant number of archaeological sites may have been overlooked in the still active agricultural communities of far western Tibet and Lake Dangra. In these regions it is plausible that successive layers of human occupation have been hidden from view by the structural overlay of contemporary settlement.

The field inspection of archaeological remains has the advantage of furnishing positive identification and the procurement of definitive empirical information. The field surveys entailed visiting virtually every one of the approximately 250 townships (reckoned according to the number of townships existing prior to the 1999-2001 period of administrative consolidation in the TAR) in the 17 counties that comprise Upper Tibet west of Nakchu city. During this twelve year campaign, I have spent nearly four years in the field, and covered more than eighty thousand kilometers by vehicle, and at least another eight thousand kilometers on foot and on horseback. In order to locate archaeological sites, individual and collective interviews were conducted in all county seats, as well as in many township headquarters, monasteries, local villages, and pastoral settlements. In the course of interviews with over 5000 people, I have met with a wide range of civil officials, monks, lay practitioners, farmers, and herders. Special emphasis was placed on allocating time to speak to those locally recognized as the most knowledgeable in their respective communities. The meticulous geographic coverage of the surveys, accomplished by canvassing large swaths of territory upwards of three to seven times each, has proven invaluable in understanding the geographic distribution of the various types of archaic cultural horizon archaeological assets in Upper Tibet.

1Before presenting an analysis of the various types of monuments, it is crucial to revisit what constitutes an archaic cultural horizon archaeological site in Upper Tibet. In brief, these are structures exhibiting physical and cultural qualities that predate the introduction and spread of Lamaism (systematized Bön and Buddhism) in Tibet. The establishment and particularly the usage of these archaeological sites, however, may have persisted for centuries after Buddhism gained a foothold in imperial Tibet (early seventh century to mid-ninth century CE). The term ‘archaic’, therefore, is employed to describe archaeological sites that exhibit non-Lamaist cultural and architectural characteristics, and not to refer to a specific time period as such.2

The provisional identification of archaic monuments in Upper Tibet is made on the basis of the following physical and cultural criteria using inferential means:

- Sites in Bön literature attributed to personages, events, facilities, and locations associated with the Zhang Zhung and Sumpa kingdoms

- Monuments attributed in local oral traditions to the ancient Bön, the Mön, personalities in the Ling Gesar epic, and the pantheon of genii loci

- Monuments exhibiting early design, constructional and morphological features

- The siting of monuments in now abandoned environmental niches

- Monuments and rock art comparable to those documented in other regions of Tibet

- Monuments and rock art comparable to those documented in other Inner Asian territories

- Art and artifacts that exhibit primitive stylistic and fabrication traits

Footnotes

Especially when used in conjunction with other archaeological criteria, Tibetan literature is a precious indicator of the location and identity of archaic monuments. Bön (and to a lesser degree Buddhist) texts are an excellent and extensive source for mythic and quasi-historical accounts relating to places in Upper Tibet supposed to have been important centers of the ancient Zhang Zhung and Sumpa kingdoms. These texts provide biographical data about the lives of Zhang Zhung and Sumpa saints, including information regarding their residences and political dealings with local potentates and foreign enemies. These literary accounts are framed in both the prehistoric epoch and early historic period, but their historicity remains obstinately difficult to corroborate. For the most part, Bön literary sources postdate the eleventh century CE (centuries after the historical events they purport to chronicle) and are heavily colored with mythic and hagiographic content, significantly limiting their value as prosaic historical documents. This literature names geographic locations, some of which can be confidently correlated to the contemporary toponymic picture (places such as Mamik, Purang, Gugé, Dangra, Tago, Tisé, Namtso, Tanglha, etc.), while the identity of others has either not been established or only tentatively. As the chronology of Bön mythic and quasi-historical materials pertaining to Zhang Zhung and Sumpa is uncontrolled (by associative events such astronomical phenomena, natural disasters, cross-cultural references, calendrical lore, etc.), it limits their use as indexes of time, except in the broadest sense.

Moreover, Bön sources have been subjected to an ongoing process of textual revision, altering the portrayal of early historical events. This modification of contents expresses itself in two major ways: the idealization of past patterns of settlement and cultural achievement, and the reconfiguration of the archaic cultural heritage using the language and concepts of Buddhism. Nonetheless, Bön literature furnishes us with valuable contextual information on major centers of early settlement and their cultural and religious complexion. For one thing, a comparison of textual-based geographic lore related to Zhang Zhung with the patterns of archaic monumental distribution in Upper Tibet reveals a strong positive correlation.

The oral traditions surrounding the archaic monuments of Upper Tibet tend to contrast with these accounts connected to Buddhist monuments, in which piety and otherworldliness prevail. Since the domination of Lamaism in Upper Tibet, circa 1000 to 1250 CE, religious attitudes developed that altered perceptions of the earlier cultural heritage of the region. Generally speaking, this recasting of history led to the archaic past being viewed with a considerable sense of fear and denial. As Buddhism and systematized Bön gradually took hold in Upper Tibet, transforming its culture and ethos, the push to reinterpret history gained momentum in society. The major effect of this historical reformulation has been to make the ancient past increasingly resemble Lamaist thought and practice. In the contemporary socio-cultural setting, the archaic monumental wealth of Upper Tibet has been compressed into just four major themes. This thematic compression involves the reduction of the ancient cultural legacy into stereotypic narratives, which now stand as supposed factual representations of the past. This has led to the loss of much historical information once associated with the archaic archaeological assets in the oral tradition of Upper Tibet. The cognitive and affective forces enmeshed in this cultural transformation were not directed at highland archaeological sites alone, but came to express themselves in manifold social and political ways across the Tibetan world.

It is within these four legendary themes that clues pointing to the identification of archaic monuments must be sought: (1) the ancient Bön, (2) the Mön, (3) the Gesar epic, and (4) the pantheon of local spirits. These legendary and mythic attributions are generally applied to sites that do not fall under the architectural ambit of Lamaist culture. They function as convenient intellectual categories to relegate awkward bits of early heritage (which by their very physical presence cannot be simply brushed aside) to a safe and distant ideological realm. While the oral tradition provides associative evidence of early settlement, it is not well suited to the collection of archaeological facts concerning archaic monuments and rock art. The oral tradition, therefore, is best applied as a non-specific and broadly inclusive interpretive anthropological tool.

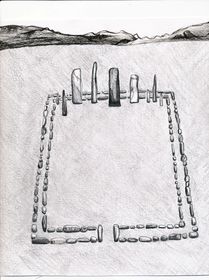

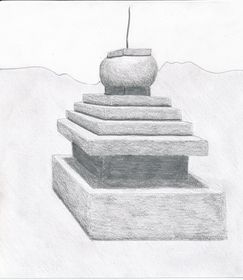

An excellent indicator of the archaic status of archaeological monuments in Upper Tibet is the presence of distinguishing features in substance and form. These physical properties reflect different architectural conceptions and modes of execution than those exhibited by familiar Lamaist monuments. Of special note are the various funerary pillars (menhirs) and necropoli of Upper Tibet. These types of monuments embody distinctive forms of abstraction and construction which do not appear to have been adopted by Lamaist adherents. A different religious ethos required an alternative assemblage of monuments: rather than large burial complexes, Buddhism and systematized Bön saw fit to cover the landscape with chöten (a type of shrine) and walls with inscribed plaques, which are of a different order of architectural magnitude. In the domain of residential monuments, great structural contrasts are seen between the all-stone corbelled edifices of early times and Bön and Buddhist buildings built with high walls and wooden rafters. Aside from the very different methods and materials used in construction, the former structures are small-chambered, windowless and semi-subterranean, while Lamaist halls and temples have larger rooms and frequently windows or skylights, and are set prominently above the ground.

The specific geographic setting of archaeological sites provides some clues to their cultural identity. Many archaic residential monuments were built at high elevation and in special environmental niches that have long since been abandoned. These sites were not the objects of sustained sedentary settlement in any way associated with the Lamaist cultural milieu of later times. A significant number of archaic sites are concentrated in defunct agricultural enclaves in far western Tibet, and on headlands and islands across the breadth of the Upper Tibetan lake belt. Archaic residential sites are also found on lofty, inherently defensible summits and ridges, or at the heads of valleys at elevations sometimes exceeding 5000m. Environmental degradation and changed cultural realities appear to be the motive forces behind the geographic shift from these specialized locations to the patterns of population distribution witnessed in more recent centuries. For the most part, the Lamaist religions chose lower-elevation basins and valleys for their major residential sites. Even when escarpments and mountain slopes were selected for the establishment of religious and political edifices, these are consistently located at a lower elevation than their archaic counterparts. Gang Tisé is an excellent case in point: all around this sacred mountain one must climb well above the existing Buddhist sites in order to reach those established in earlier times. The same patterns of settlement hold true for Dangra Yutso where the archaic cultural horizon looms over the contemporary Bön villages.

Comparative study of Upper Tibetan archaeological assets, with their counterparts in Central Tibet and Eastern Tibet, is another tool for ascertaining relative age and cultural affiliations. Unfortunately, very little reliable chronometric data has yet been assembled for archaic residential and ceremonial sites located in other regions of Tibet. Moreover, comprehensive archaeological surveys have yet to be launched outside Upper Tibet. The poorly organized archeological data compiled in other regions of the plateau impedes studies based on cross-referenced archaeological comparisons. As a result, the extent and nature of paleo-cultural affinities between Upper Tibet and Central Tibet and other regions of the plateau have not been adequately determined.

In Upper Tibet and Central Tibet, quadrate burial tumuli with inwardly sloping walls were built in the early historic period and most probably in the prehistoric epoch as well. However, the all-stone corbelled residential edifices and pillar monuments that define the Upper Tibetan paleo-cultural territory are not represented in Central Tibet. Kham and Amdo have varying assemblages of monuments (these are still not well catalogued). Nevertheless, the pastoral regions of Amdo were host to a rock art tradition that is thematically and stylistically related to that of Upper Tibet. The areal variability marking archaeological assets is acknowledged in the Tibetan historical tradition, which assigns prehistoric Central Tibet and Dokham to different proto-tribal or quintessential groupings. Central Tibet is recorded as being dominated by Bö, Kham by Minyak, and Amdo by Azha.

Cross-cultural Inner Asian study is a fecund methodological approach for the determination of the identity and chronology of Upper Tibetan archaeological assets. This method has proven best suited to the interregional comparison of funerary sites that possess substantial above-ground structural elevations. Archaic funerary pillars and slab wall structures are a case in point, where comparisons between the Upper Tibetan, Mongolian, Altaian and south Siberian types have borne good results. These basic monumental forms are dispersed throughout Inner Asia. As in other spheres where the technologies and cultural traditions of Inner Asia were disseminated widely, chronological and cultural parallels between the funerary monument traditions of Upper Tibet and adjoining regions are indicated. The comparative study of Inner Asian rock art is useful in delineating the amalgamative processes that brought Upper Tibet into functional and aesthetic congruity with its northern neighbors. The biggest drawback to cross-cultural analyses remains the general shortage of good chronological controls for sites in Upper Tibet. This will be remedied only when chronometric studies gain sufficient ground.

The aesthetic and technical analysis of art and artifacts is best used in conjunction with collateral archaeological data, but even alone it is a helpful method for estimating chronological values. The rock art record provides one of the best indexes of cultural evolution from the archaic to the Lamaist. The prehistoric Upper Tibetan rock art tableaux are rich in compositions that depict economic, environmental and cultural matters related to the way of life in the region. These petroglyphs and pictographs are largely unrelated to Buddhist-inspired art and design as they developed in Tibet. Rock art exhibiting archaic themes (such as hunting scenes, the isolated portrayal of wild animals, and iconic motifs) continued to be produced well into historic times. This suggests that there was a good deal of cultural continuity between the prehistoric and historic epochs in Upper Tibet. Nonetheless, analogous subject matter reveals different modes of manual execution and stylistic presentation, valuable evidence in any attempt at chronological differentiation. As compared to rock art made in the prehistoric epoch, the later variants exhibit their own set of production qualities and aesthetic refinement. Rock art of the historic epoch is either cruder or more polished. This inferred chronological progression is also discernable in other spheres of material culture. Copper alloy artifacts such as amulets, implements and weaponry possess aesthetic and technical features indicative of relative age and cultural affiliation as well.

In addition to these indirect means of assessing archaic cultural status, the radiometric and AMS assaying of organic remains recovered from sites constitute the direct approach to dating. The criteria outlined above are all dependent on inferring chronological information from evidence that does not intrinsically lend itself to scientific verification. For these criteria to be validated, the conclusions drawn from the cultural identity, appearance and location of monuments and rock art must ultimately stand the test of chronometric verification. Over the last four years, I have begun the process of independent corroboration of the suppositions set forth above. I am intent on presenting the identification of the corpus of archaic structural and aesthetic forms in Upper Tibet in a more objective and reproducible fashion. In pursuance of this goal, 20 samples have been submitted for radiometric and AMS analysis (derived from both residential and ceremonial sites). The recovery and archaeometric assaying of far more samples from many more sites is demanded to definitively chart the chronology (and other objective values) of the Upper Tibetan archeological assemblage. Archaeometric inquiry is also essential in weeding out those sites that may not have an archaic cultural horizon status. It is on a good footing that chronometric data assembled thus far have begun to corroborate the presumptions made concerning the temporal orientation of the sites surveyed.

1The assembled chronometric and collateral data indicate that Upper Tibetan archaic monuments and rock art were produced over a wide spectrum of time, in both the prehistoric and historic settings. Two major epochs, each with two cultural phases, are provisionally indicated. The archaic cultural horizon spans both the prehistoric epoch and the early historic period:

- I) Prehistoric epoch

- i) Iron Age

- ii) Protohistoric period

- II) Historic epoch

- i) Early historic period

- ii) Vestigial period

Footnotes - ^ This section of the work is also derived from Bellezza, Zhang Zhung.

The first phase of the prehistoric epoch includes those sites that were founded in the early Iron Age (first half of first millennium BCE), and the developed Iron Age (middle and late first millennium BCE) of Inner Asia. Possibly, late Bronze Age (circa 1200 to 800 BCE) affiliations are also indicated in the first phase of prehistoric Tibetan civilization, but this remains difficult to corroborate.1 A treatment of more remote prehistoric epochs (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) falls outside the purview of the current study.2 The second or later phase of the prehistoric epoch corresponds to an anachronistic extension of the Iron Age, marked by the Central Tibetan line of kings (late first millennium BCE to the seventh century CE). This second phase of the prehistoric epoch can be termed the protohistoric or legendary monarchal period, due to the many Tibetan literary records that refer to the Central Tibetan kings of that time. There are also Bön texts purported to have been written in this time frame, though solid evidence for this allegation is lacking. These literary records include some assumed to have been first written in the Zhangzhung and Sumpa languages, which came to be translated into Tibetan during the imperial period. According to the Tibetan historical tradition, the plateau of the Iron Age was divided into a number of petty states and governed by a succession of demigod chieftains. The protohistoric period in turn, is marked by the rise of the yar lung or Pugyel dynasty beginning with King Nyatri Tsenpo (traditional chronologies place him in the circa 200 BCE period).

- ^ At present the scant chronometric data do not demonstrate that any of the archaeological sites surveyed date to the late second millennium BCE or earlier. I suspect, however, that this current age limitation will be overcome as the pace of archaeological research intensifies and Bronze Age (especially late Bronze Age) structures can be positively identified. As in Central Tibet, some Upper Tibetan monuments may even prove to date to the Neolithic. An earlier periodization is particularly likely for tombs, because in all adjoining regions where chronometric and collateral archaeological data have been assembled, there are burials that predate the first millennium BCE. Another possible exception to an early Iron Age chronological basement are certain Upper Tibet rock art sites and compositions, which in terms of the techniques of manufacture and style conform to what some Central Asian rock art specialists would consider to be Bronze Age schema.

- ^ For reviews of these earlier epochs see Aldenderfer, “The Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau”; Chayet, Art et Archéologie du Tibet. Sites attributed to the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic have been discovered in Upper Tibet, but far more research is needed to determine when the high plateau was first peopled and how these earlier occupations contributed to the later course of civilization in the region.

This first phase of the historic epoch, the early historic period, chronologically corresponds with the Tibetan empire or imperial period and its troubled aftermath (seventh century to the end of the tenth century CE). It was in the imperial period that the definitive introduction of Buddhism (tenpa ngadar) into Tibet, the development of the Tibetan system of writing (bö yigé), and the expansion of Tibetan political power across the entire plateau and beyond occurred. The Upper Tibetan proto-states of Zhang Zhung and Sumpa were absorbed into the pan-Bodic polity of this period as well. The vestigial period includes all archaic style monuments and rock art that continued to be founded in Upper Tibet (late tenth century to mid thirteenth century CE). The production of some archaic cultural horizon archaeological assets appears to have continued for some centuries after the collapse of imperial Tibet. Certain surveyed tombs, strongholds and religious edifices are likely to fall into this category. These architectural anachronisms seem to have been a cultural counterpoint to the inexorable process of Lamaist transformation. This period in Tibetan history is characterized by political reconsolidation, such as the formation of the Buddhist Gugé state in western Tibet in the late tenth century CE, and the ascendancy of the Sakyapa in the early thirteenth century CE.

At this juncture, the chronological values proposed above remain largely hypothetical, and with the exception of those few sites where chronometric data have been forthcoming, inexact and open to amendment. Nevertheless, this provisional chronology indicates that archaic cultural horizon archaeological monuments in Upper Tibet are a highly diverse group in terms of age and composition. By virtue of straddling the prehistoric and historic divide, the sites surveyed represent a heritage of varying environmental dimensions, social forces, religious persuasions, and political orders, which are emblematic of cultural change in Upper Tibet over a period of no less than two millennia.

This work primarily treats the typological aspects of the study of archaic monuments and rock art as the basis for their periodization. Additional study, involving the vigorous application of chronometric methodologies, will be needed to create a precise chronology for each of the monument and rock art types surveyed. It is through such study that the cultural development of Upper Tibet and the nature of its intercourse with adjoining territories will come to be known in the kind of detail that such an important piece of the world’s ancient heritage deserves. In addition to providing a model of cultural transition and adaptation in Upper Tibet, chronometric inquiry is required to determine the impacts of Late Holocene (circa 2000 BCE to present) climatic deterioration on the various archaeological sites. Material culture studies are another area of archaeological research that has barely begun. The scientific recovery and study of utilitarian and ritual objects is of the utmost importance if we are to flesh out the cultural specifications, periods of usage and environmental determinants at work at each of the sites catalogued.

Herein is an outline of the archaic cultural horizon monument and rock art typologies distributed above the ground in all areas of Upper Tibet. The monument typologies fall into two major divisions: residential (structures in which people resided or temporarily lived) and ceremonial (non-residential structures chiefly used for religious and burial purposes). Residential monuments are further divided according to their primary design traits and situational aspects. Ceremonial structures are subdivided according to their morphological and functional aspects. In Upper Tibet there are also minor physical remains associated with the ancient agricultural economy. Earthworks located in Damzhung and Nyingdrung may have had a residential and/or ceremonial function. Rock art of all types forms the aesthetic or graphic division of Upper Tibetan archaeological assets, while rock inscriptions are the epigraphic component.

- I. Residential Monuments

- 1) Residential structures occupying summits (fortresses, breastworks, religious buildings, palaces, and related edifices)

- a. All-stone corbelled buildings

- b. Edifices with roofs built from timbers

- c. Solitary rampart networks

- 2) Residential structures in other locations (religious and elite residences)

- a. All-stone corbelled buildings

- b. Other freestanding building types

- c. Buildings integrating caves and rock overhangs in their construction

- 1) Residential structures occupying summits (fortresses, breastworks, religious buildings, palaces, and related edifices)

- II. Ceremonial Monuments

- 1) Stelae and accompanying structures (funerary and non-funerary)

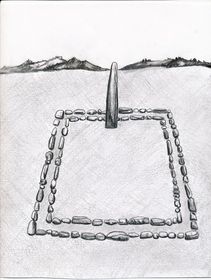

- a. Isolated pillars (doring)

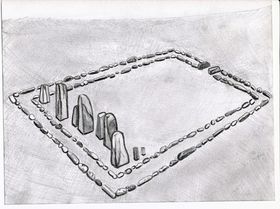

- b. Pillars erected within a quadrate stone enclosure

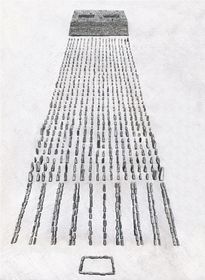

- c. Quadrangular arrays of pillars appended to edifices

- d. Domestic pillars

- 2) Superficial structures (primarily funerary superstructures, burial and non-burial in function)

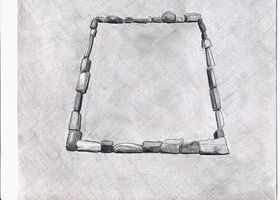

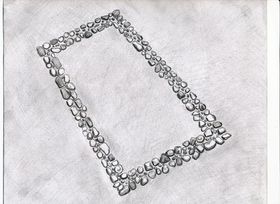

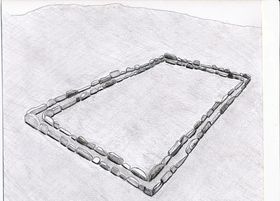

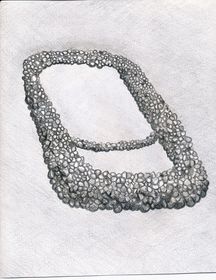

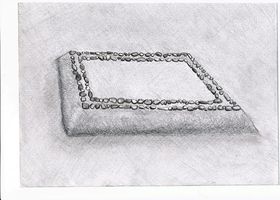

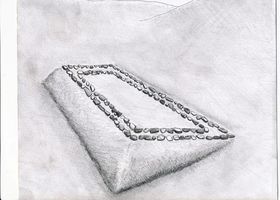

- a. Single-course quadrate, ellipsoid and irregularly-shaped constructions (slab wall and flush-block)

- b. Double-course quadrate, ellipsoid and irregularly-shaped constructions (slab wall and flush-block)

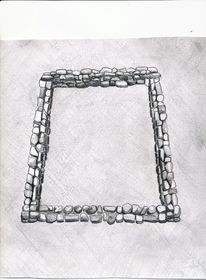

- c. Heaped-stone wall enclosures

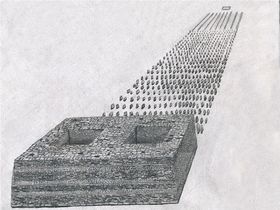

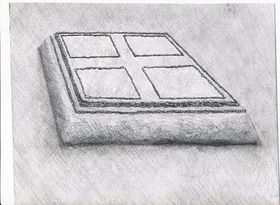

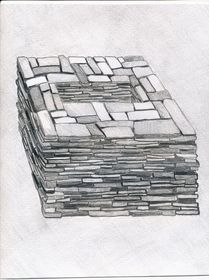

- d. Quadrate mounds (bangso)1

- e. Terraced constructions

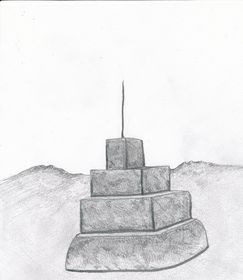

- 3) Cubic mountaintop tombs

- 4) Shrines and miscellaneous constructions

- a. Stone registers (to)

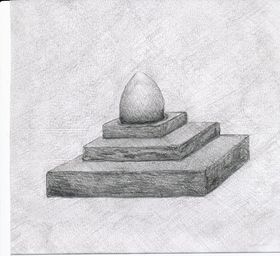

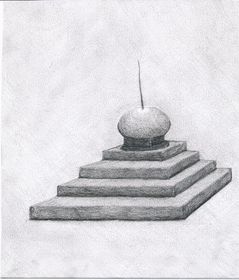

- b. Tabernacles (lhatsuk, sekhar, lhaten, and tenkhar)

- 1) Stelae and accompanying structures (funerary and non-funerary)

- III. Agricultural Structures

- 1) Stone irrigation channels

- 2) Terracing

- a) Retaining walls

- b) Partition walls

- IV. Earthworks

- 1) Rampart-like walls and platforms

- V. Rock Art and Epigraphy

- 1) Petroglyphs

- 2) Pictographs

- 3) Inscriptions and ciphers

Footnotes - ^ For the purposes of this study, the Tibetan term bangso is only used to denote burial mounds. In the Tibetan language this term can also be applied to a larger range of burial structures.

See footnote for information on this section of the text.1

- ^ This part of the work is based on John Vincent Bellezza, “A Cornerstone Report. Comprehensive Archaeological Surveys Conducted in Upper Tibet between 2001 and 2004. Documentation of archaic monuments and rock art in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Carried out under the auspices of the Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences and Ngari Xiangxiong Cultural Exchange Association of the Tibet Autonomous Region,” Tibetan & Himalayan Library (URL not currently available. 2005). For more detailed typological and paleocultural information, see Bellezza, Zhang Zhung.

This division of archaeological sites includes all types of monuments that were designed and built for residential activities. Within this division are those monuments that were used for human habitational activities, whether of an economic, political, religious or domiciliary nature. In a land where much of the population is likely to have lived in tents and other temporary shelters from time immemorial, permanent habitation in well-built edifices must have largely been the domain of the higher strata of society. In this work, information on 162 residential sites is presented.

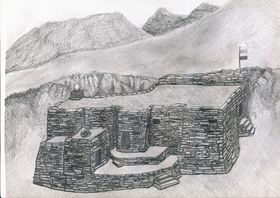

In this residential type are all habitational structures located on the summits and prominences of mountains, ridges, hills, and high rock formations. By the very nature of these geographic locations, such monuments have an inherent defensive aspect to a lesser or greater extent. Among this residential type are edifices that functioned as fortresses and citadels (habitations designed and built for military purposes), temples and hermitages (buildings with a religious or ceremonial function), palaces (social elite residential buildings), and breastworks (networks of ramparts or other types of defensive structures that were temporarily or permanently inhabited). It must be noted that, from a visual appraisal alone, the specific occupational functions of individual edifices or components thereof can only be inferred. In any event, these strongholds, temples, palaces, and hermitages appear to have been where the ruling and priestly classes exercised their social influence and political control over the agriculturalist and pastoralist sectors of society.

I.1a) All-stone corbelled buildings

This building subtype represents one of the most prominent classes of residential structures found in Upper Tibet. In the parlance of the region, this style of architecture is often referred to as dokhang (all-stone habitation). This form of construction is characteristic of the archaic cultural milieu of the region, and is eminently well suited to the environmental exigencies of the harsh landscape. It is in Upper Tibet that all-stone corbelled buildings reached their fullest architectural expression in all of Central Asia. This building design is exceptionally rugged and structurally stable, and individual examples may, in some cases, have endured as habitations for centuries.

All-stone structures feature the use of corbels, stone members that were placed on the upper extent of walls as load bearing devices for the stone roof assembly. Corbels were simply rested on the tops of walls or were inserted into specially built wall sockets. Corbels act to support bridging stones and stone sheathing from which the roof was made. Bridging stones were laid diagonally or crosswise in one or more courses over the corbels in order to span the distance between opposite walls. In turn, large slabs of stones were placed upon the bridging stones to create a complete roof covering. The elementary corbelling technique employed in Upper Tibet for roofs was only suited for use over small interior spaces (typically 3 m² to 12 m²). Large edifices were created by juxtaposing multiple, structurally self-contained rooms or groups of rooms together to form a contiguous ground plan. In some places (such as sites A-10 and A-54) corbels with sockets were used to support the stone flooring of a second story in the same fashion as roofs were constructed.

All-stone corbelled edifices have many unique design traits. In general, they are massively built, a consequence of the great weight that the roofs bear on these structures. Walls are between 60 cm and 1.2 m in thickness, and of a slab or block random-rubble texture. Both dry-mortar and clay-mortar seams are represented in their construction. Roofs are, as a matter of course, flat and originally must have been layered in gravel and clay to weather-proof the buildings (little evidence of this more ephemeral aspect of construction has survived). As each room or group of rooms is an isolated unit structurally, the exterior walls of such structures have an irregular or even a meandering plan. Walls are of variable thickness, with various exterior indentations and interior recesses common. Both exterior and interior corners tend to have a rounded quality, as this facilitates the arrangement of corbels. Interior walls are punctuated with buttresses that function to support intervening series of corbels and roof appurtenances, especially in larger rooms. The floor-to-ceiling height of rooms in dokhang is usually relatively low (1.6 m to 2 m). Most buildings are windowless and even in certain structures where there are interior and exterior window openings, these are small in size.

Single buildings contain between two and one dozen rooms, which are normally arranged in rows or isolated aggregations. Rooms directly open onto one another or are connected through a small corridor or interclose. Various wings in a single building usually had separate exterior entrances, as large interconnecting halls and galleries are not possible in dokhang construction. Another defining feature of the all-stone corbelled edifices is the very small size of their doorways; these average only around 1.1 m in height. The lintels of the entranceways (and the few windows) are made from stone. The heavy windowless walls and low doorways of the rooms indicate that they must have been weatherproof and easy to heat. Collections of small rooms also indicate that a decentralized or compartmentalized domestic ecology was the norm. Individual cells must have been set aside for the various facets of everyday life such as sleeping, food preparation, storage of provisions, and religious observances. Rooms were only large enough for individuals or small family units. Cooking, meetings and ceremonial life inside the dokhang could only have revolved around small groupings of people.

Customarily, sundry dokhang on a summit were vertically interconnected to create a staggered array of structures. Naturally occurring rock outcrops and ledges were commonly used to help support corbelled buildings and to act as one or more walls of the structure (particularly in the rear). This form of construction is very favorable to incorporation into the adjoining terrain, as walls could be built to accommodate the twists and turns of rock faces. This high degree of integration with the parent formation is a distinguishing feature of dokhang design. Although corbelled edifices individually have low architectural elevations (there are no high ceilings in rooms, and parapet walls where they exist appear to have been minimal), the stacking of one on top of another has the effect of producing formidable complexes. It is not uncommon to find these clinging to the sheer walls of a summit for many vertical meters. In sites that appear to have functioned as hermitages, individual residences tend to be separated from one another rather than forming aggregated complexes. The use of prominent revetments, a common feature, significantly increased the elevation of exterior faces. Revetments function to give buildings a stable foundation and to even out the dips and rises on rocky summits. Rather infrequently, all-stone edifices were integrated with other building types at a single site. Occasionally, there is also evidence to suggest that the basement or lower story of a building was fashioned as a dokhang, while the superstructure was of an alternative style of construction (see site A-51).

The wide distribution of dokhang through most areas of Upper Tibet and their superb adaptive bearing indicates that they were a chief residential type for a long period of time in the region. Bronze Age occurrences of corbelled edifices in regions like the British Isles and Mediterranean may suggest that this form of architecture developed in Upper Tibet at a relatively early date. The lack of demonstrable monumental precedents in the archaeological record of Upper Tibet reinforces the impression that all-stone edifices have a very long legacy behind them. Chronometric data on the sites surveyed are now undergoing compilation; these results furnish the best archaeological evidence corroborating the archaic nature of Upper Tibet’s all-stone edifices.1

I.1b) Edifices built with timbers

This heterogeneous monument subtype includes all residential structures that were built with roofs containing timbers. Among the examples included in this inventory may be sites that were actually founded or redeveloped after the early historic period that could not be differentiated from older strongholds (because of the possession of similar morphological and cultural attributions). Further archaeological investigation will be required to clear up this typological ambiguity. Edifices constructed with wooden roofs located on summits generally have a good defensive posture. As with the all-stone corbelled structures, their domiciliary usage appears to have varied greatly. Citadels, fortified settlements, temples, and palaces are all probably represented among this class of habitation. These timbered edifices are of four major wall fabrics:

- Random-rubble and coursed rubble stone walls

- Adobe or unbaked mud block walls (sapak)

- Rammed-earth or shuttered walls (gyang)

- Walls of cut earthen slabs

i) Residential structures built with stone walls are commonly encountered throughout Upper Tibet. Where walls are left standing, this type of construction is readily identifiable: walls are straight and regular and can be of considerable length. As roofs were built with wooden timbers, the walls supporting them were not required to be as massive as structures with much heavier all-stone roofs. The regular buttressing and indentations of dokhang walls is also conspicuously absent. Moreover, high elevation profiles and large rooms and halls are found with much frequency, especially among Buddhist complexes. However, what appear to be archaic structures built in this manner share some of the customary features of dokhang design. These include edifices with smaller rooms, windowless walls, relatively low entranceways, adeptly constructed random-rubble slab walls, a high degree of topographical integration into the parent formation, the proliferation of small buildings staggered vertically across a summit, and series of small ramparts.

None of the stone wall buildings surveyed have their roofs intact but the general constructional pattern and the rare presence of timber fragments suggests that roofs were constructed much as they were in the Central Tibetan style of architecture. This entails the laying of timbers across the top of walls and covering them with wooden and/or stone interlinking materials. Once the roof was completed in this fashion, wattle, clay and possibly Tibetan cement (arka) must have been used to build successive enclosing layers. Unlike the traditional architectural landscape of Central Tibet and Eastern Tibet, there is no evidence of towers having been erected in Upper Tibet, stone buildings of more than two stories being rare in the region.

A site attributed to the ancient Mön in the oral traditions of Upper Tibet Kapren Gyanggok (A-33) was in use as late as the 13th century CE. Chronometric data obtained from Kapren Gyanggok reinforces the view that monuments attributed to the Mön must be understood in a broad historical and cultural framework.

ii) Residential structures built with adobe blocks are commonly encountered in Gugé, that large Transhimalayan badlands region in the Sutlej (Langchen Tsangpo) drainage area of deep gorges and highly eroded earthen formations. While mud-brick walls are common in Buddhist era buildings (such as monasteries and retreats) in the Jangtang, there is scant evidence that such structures were established in pre-Buddhist times. One exception may be a complex of buildings at Drakgam Dzong (B-40). It was founded on a slope overlooking the Mukyu Tsangpo basin, a rich pastureland.

Adobe block edifices were founded in great numbers in Gugé in the Buddhist era. According to the local oral tradition, they were established in the prehistoric epoch and had been the handiwork of that elusive tribe the Mön or Kel Mön/Kel Mön.2 From an environmental perspective, this claim of antiquity for elementary earthen structures is plausible, for building stones are in short supply in many corners of Gugé, and lithic materials appropriate for corbelling and bridging only very seldom occur. The antiquity of adobe block constructions is also supported by recently compiled chronometric data from the Rula Khar site (A-141) (see below). Systematic survey of sites in Gugé, to which oral tradition assigns an archaic identity, has brought to light physical evidence, which tentatively permits adobe structures to be chronologically differentiated from one another. One distinguishing criterion employed in trying to determine what may be examples of archaic adobe edifices is based on an analysis of building design. Sites such as Hala Khar (West) (A-58) strongly contrasts with known Buddhist architecture of the region. Its highly exposed and isolated aspect, unusual ground plan and extremely deteriorated condition are circumstantial evidence for the inclusion of Hala Khar (West) in the category of archaic monuments. This single 32 m long contiguous complex consists of four rows of tiny rooms that run parallel to the axis of the summit at different levels. No Buddhist monuments or emblems are found at Hala Khar (West) and no Buddhist religious lore is attached to the site.

The survey of citadels and other summit residential structures attributed to the ancient Mön in the localized traditions of Gugé demonstrates that most of the facilities exhibiting mud brick wall construction are in fact primarily built of stone. At most so-called Mön sites adobe walls were used for relatively minor constructions and for upper wall courses. What adobe walls do exist are as a rule much more highly eroded than Buddhist constructions. At none of theMön castles (möngyi khar) are there large, high-walled buildings (lhakhang, dükhang, etc.) like those found at virtually every Buddhist monastery in Gugé. Moreover, sites attributed to the archaic period of construction are often associated with troglodytic communities with few or no signs of Buddhist occupation. A foundation or refurbishment date of circa 565 to 705 CE is indicated for the adobe block northwest edifice of Rula Khar (A-141). The relative position of the radiocarbon assayed sample in the building confirms that adobe block constructions were indeed part of the archaic architectural canon of Gugé.

iii) Rammed-earth residential structures that local oral tradition places in the archaic period are limited in geographic range to lower elevation western Ngari Korsum and in particular, to Gugé. A single wall of this construction type attributed in the oral tradition to the Zhangzhung kingdom is found at the high point of the Takla Khar fortress (A-81) in Purang. In Gugé, summit strongholds such as Jangtang Khar (A-116) and Sharlang Khar (A-118), two castles that in the local oral traditions are assigned to the Kel Mön, have rammed-earth structural remnants. Walls of this type, nevertheless, are found at only a minority of strongholds attributed to the ancient Mön in Gugé. The technological origin and chronology of rammed-earth walls, built by packing wet earth and clay with a stone matrix between large wooden shutters, is not at all certain. It may be that rammed-earth structures are wrongly attributed in legend to the archaic period or that they were founded at sites with structural remains from earlier periods of occupation.

iv) At just a few fortified sites in Gugé another type of wall was formed from naturally occurring compressed slabs of earth, which were cut from the native formations. Structures built with this type of wall dominate at Cholo Puk (A-113) and Rakkhashak Möngyi Khar (A-115), strongholds attributed by local residents to the Mön. At Cholo Puk, a sequence of chambers were cut out of the long flat summit, and the slabs resulting from the excavation used to build walls above the top of the excavated chambers. Parapet walls were also built around the edges of the summit using the same natural earthen slabs. The absence of monuments indicative of Buddhist occupation at these sites, as well as their semi-subterranean aspect, encourages the view that earth slab fortifications do indeed date to the era of archaic residential structures.

I.1c) Solitary rampart networks

Some strongholds in Upper Tibet are exclusively composed of networks of defensive walls traversing summits and adjoining slopes. At sites such as Namdzong (A-48) and Takzig Nordzong (A-50) there appear to be few, if any, residential buildings, but rather a series of ramparts fortifying a strategic mount or rock formation (those in proximity to a high quality pasture or important pass). These random-rubble dry-mortar breastworks consist of long walls that wind across slopes vulnerable to attack. Typically, the walls are 1 m to 2 m high on the downhill slope, and slightly elevated or flush with the uphill side of a slope. These defensive structures are normally around 1 m to 2 m in width, and between 2 m and over 100 m in length. Parapet walls or ledges were probably built on the outward projecting edge of the ramparts but much of the structural evidence for these features has disappeared down the slopes with time. A chief characteristic of rampart network design and deployment is that they appear in multiples, each wall running in a transverse direction at different elevations and somewhat parallel to one another. An approachable slope may have upwards of eight successive ramparts, one above the other, guarding the higher and more vital reaches of a site. In addition to being aligned in parallel, defensive walls join one another or branch out in different directions across ribs of rock and broad acclivities. Some of the wider, more level and sheltered breastworks appear to have functioned as platforms for camps and the garrisoning of fighters. The intricate arrangement of breastworks as the exclusive or dominant architectural component of a fortified site bespeaks a special form of defensive posturing by which entire rock formations functioned as strongholds.

While some sites seem to have been comprised entirely of breastworks, most of the archaic fortifications of Upper Tibet heavily relied on them for defense. At many citadels, defensive walls form an integral part of the complex. These are of three major types: 1) those staggered below residential structures that are erected on a summit; 2) those that encircle the main nucleus of habitation (circumvallations); and 3) those that connect various residential structures (curtain-walls).

- ^ On the basis of similarities in size, orientation and ground plan, as well as the presence of an interior pillar marking an analogous area in the Dindun site (Dingdum) habitation S4, Mark Aldenderfer infers that the ‘Founder’s House dokhang’ (part of site B-13) may date to the same period, circa 550-100 BC (Mark Aldenderfer, “A New Class of Standing Stone from the Tibetan Plateau,” The Tibet Journal 28, nos. 1-2 [2003]: 3-20). A small round of wood was discovered in the stone rubble of a semi-subterranean dokhang at the Gekhö Khar lung site (A-89). This specimen has yielded a calibrated radiocarbon date of circa 200 BC to 100 CE. The historical persistence of dokhang as active residences until the early second millennium CE, is indicated in the contest between Buddhist yogin Milarepa and the Bön adept Naro Bönchung (Bellezza, Antiquities of Upper Tibet, 65).

- ^ An important textual reference concerning the historical identity of the Kel Mön of Upper Tibet is found in Mar lung pa rnam thar, written by Thon kun dga’ rin chen and Byang chub ’bum (13th century CE). For this reference, a translation, and bibliographic information about the text, see Roberto Vitali, The Kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang. According to mNga’.ris rgyal.rabs by Gu ge mkhan.chen Ngag.dbang grags.pa (Dharamsala: Tho.ling gtsug.lag.khang lo.gcig.stong ’khor.ba’i rjes.dran.mdzad sgo’i go.sgrig tshogs.chung. 1996), 200 (n. 287), 589. It must be noted that Vitali’s translation of the passage under question differs in a number of important areas from the one I provide below. Vitali maintains that the concerned passage documents a group of northerners distinct from the Kel and Mön, for which there is little grammatical basis. In his excellent study, Vitali may have been persuaded to translate the passage in such a way because of various other historical references that place the Kel Mön in Himalayan regions. The Mar lung pa rnam thar records that the Mön and another group known as the Kel were pushed out of northern areas of Tibet by the Hor (probably a Central Asian Turco-Mongolian group), forcing them to settle further south (in Gugé?). According to Vitali’s analysis, this event occurred between the demise of the Tibetan empire and the founding of the Ngari Korsum kingdom by Nyima Gön, in the early tenth century CE (Vitali, Kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang). Evidently, in their new homeland the Kel and Mön, Bön practitioners, became amalgamated into one tribal entity. This account provides a historical basis for the pervasive Upper Tibetan oral tradition, which holds that the Jangtang was once widely populated by the Kel Mön. This Mar lung pa rnam thar account also documents the creation of a castle by the Kel Mön, but unfortunately it is not referred to by name or location. The text reads as follows: “…The four mountains of Kel [and] the thirteen tongdé (divisions of 1000) of Mön were the people of the north. They were driven out of their country by the Hor and arrived in the southern districts. They settled in different places. They built a great castle. The Kel Mön king Yukha received empowerments and transmissions (these teachings were received from Tönmi Nyima Özer, a Zhang Zhung Nyengyü master who was alive in the late ninth century CE). He produced a Bön Kham Chen (a sixteen-volume collection analogous to the Buddhist yum) in gold lettering” (skal gyi ri bo bzhi/ mon stong sde bcu gsum/ byang gi mi yin pa hor gyis yul ston lho ru sleb/ yul so so btab/ mkhar chen po rtsigs/ skal mon gyi rgyal po g.yu khas dbang lung zhus/ bon khams chen gser ma zhengs/; Vitali, Kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang,200, 222).

This type of residential site includes all monuments situated in any geographic locality other than those set on top of summits. Such habitations are found on broad slopes (those with higher ground in the immediate area), valley bottoms, ravines, gorges, benches, esplanades, headlands, and at the foot of or in escarpments and outcrops. However, such sites are seldom found in the midst of large exposed plains. The same kind of constructional and design elements exhibited by the summit residences are part of this category of archaic sites. The majority of them appear to have been habitations for religious and other high social status forms of residency. We might expect that, when most of the population of the Jangtang was housed in black yak hair tents (dranak) and other types of temporary shelters, the occupation of highly weatherproof permanent habitations was a mark of social distinction and achievement. This, indeed, was the state of affairs in the pre-modern Jangtang. Cave residences are found throughout Upper Tibet, but in numbers that would not have permitted more than a small fraction of the total population to avail themselves of such facilities in any given period (with the notable exception of Gugé with its many thousands of caves).

I.2a) All-stone corbelled buildings

These edifices are of the same design and construction as those perched on summits, the main difference between them being situational in nature. As such, all-stone corbelled buildings or dokhang located away from high ground lack a strong defensive aspect. Functional differences in the kinds of occupancy may be implied by these locational contrasts. All-stone edifices removed from summits tend to be individual dwellings separated from one another by meters or tens of meters of distance. This contrasts with the clustered plan of many summit sites.